A Look at History

Of the fifteen provinces of historical Armenia, precisely described by the 7th-century geographer Anania Shirakatsi, Artsakh is the most recent to have been emptied of its Armenian population. As is customary in the region, particularly in Turkey, this eradication is accompanied by a systematic effort to erase traces of the millennia-old Armenian presence, with monumental heritage being the most visible part of this process.

The eradication of the Armenian presence is, in fact, a central element in the construction of an “Azeri” identity, a contemporary term used to refer to the “Tatars of the Caucasus.” This destruction sometimes takes slow forms, such as the implementation of a policy of insidious harassment, encirclement/enclavement, and infrastructure projects that render Artsakh entirely dependent on the power in Baku—this was the case during the brief history of the USSR—and, more broadly, an undisguised racism carefully maintained by local authorities.

In some respects, the political elite currently in power in Baku is the heir to the Young Turk elite, which gave birth to a Soviet “Azerbaijan” to which both Nagorno-Karabakh and Nakhichevan were attached with the complicity of the Caucasian Bolsheviks. This elite legitimizes itself by methodically employing a revisionist discourse, widely echoed by a significant portion of intellectual elites, with, until recently, the complicity of European academics. In fact, they share a denialist policy regarding the 1915 genocide.

As part of this long process, the Kemalists even went so far as to acquire, through a territorial exchange with Iran, a narrow strip of land connecting Turkey to Nakhichevan. Methodically, the two states are advancing their agenda, and after uprooting the Armenian populations from Nagorno-Karabakh, they are now targeting the territorial integrity of Armenia itself.

This exhibition illustrates the catastrophe experienced by the people of Artsakh, as well as the profound indifference of the international community in the face of these events. The lesson to be drawn from these events is clear and must be set in stone: one must be capable of deterrence in order to survive in peace.

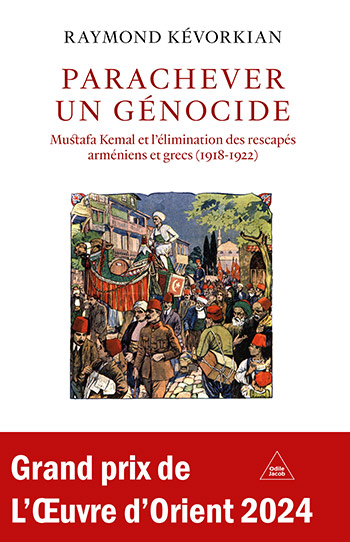

Awarding of the 2014 L’Œuvre d’Orient Literary Prize to Raymond Kevorkian for his book « Parachever un génocide », published by Odile Jacob.